1) This is my story

At intermission of my first “Wall” concert, two 20-somethings sitting in front of me excitedly turned around, eager to share their experiences and feelings. They’d been hugging one another and hooting and pumping their fists as their favorite songs came up, as the incredible spectacle unfolded before them.

My concentration was focused on the names and pictures being projected on the just-completed wall. I hadn’t been expecting the up-to-date anti-war message present in Act One (and about to be amped up for the first half of Act Two).

The one-sided exchange was the female of the couple raving about how amazing the show was. I was still trying to process things. I wasn’t expecting an up-to-date and relevant presentation. I thought it would be at best a last-gasp spectacle of 1970s and 80s arena rock excess, and I was good with that going in.

All of a sudden, it was all different. My brain was scrambled.

And here was an enthusiastic college-age woman, bedecked in some kind of headband antennae, and enough glitter to keep a manufacturing company in business for a month, and she determined we were going to have a conversation.

“Did you like that?” she said.

“I think it may have been the greatest hour of a concert I’ve ever seen,” I said.

When Grandpa, who’s clearly been to his share of shows and someone else’s as well, makes that kind of declaration, the youngsters sometimes sit up and take notice.

“Do you have anybody here with you?”

Now, I don’t know what prompted this question. To this day, five years later, I still find it one of the more curious concert interactions I’ve had. And I wasn’t prepared for the truthfulness of my answer.

“Nope,” I said. “This is my thing. For 30 years, I’ve wondered what this show was. I didn’t want to share it with anyone, I don’t want to listen to what anybody else thinks, I want to watch it and process it. There is no one I know who has the feelings about this work that I do. And he just spent an hour changing some of those feelings.

“This is my story.”

Her reaction was wholly unexpected.

“I think that’s so cool,” was her sole sincere response.

“Nah,” I said. “I can think of a half-dozen people who would like to see this, and who would enjoy it as much as I am. I could have asked a couple of them to come along. I’m really being selfish. This is a dick move.”

Her eyes locked with mine, and she slowly shook her head.

“It’s not ‘a dick move’,” she said. “It’s really special.”

I thanked her for the exoneration.

I was thinking about her two years later, when I drove to Chicago to see the show again, this time in Wrigley Field. I’d asked a couple of people if they wanted to go, but didn’t exactly chase after them. By the time tickets went on sale and I hadn’t heard back, I was just as relieved to order one ticket.

The album has sold millions of copies. The show has been seen by a few hundred thousand. Yet, I can’t think of many other pieces of art that I find so strikingly personal for myself.

As I rode with two people to see the documentary film, I told my fellow passengers, “I think I’ve probably published 35,000 words about ‘The Wall’ in the paper.” (And they’ve ALLOWED THAT without any threat of discipline. Either I’m really fucking good, they don’t know what I’m talking about, or no one’s paying attention. Or some combination of those three.) “If you have any questions about the album or the show, I think I can help.”

Hubris. Selfishness. Elitism. That’s a lot of what I bring to the discussion of “The Wall.”

None of which negates anything I’m about to say. In fact, I might be better equipped to make these observations and analyses than anyone else you know.

Hubris.

2) This is exactly the story Roger Waters wanted to tell

“The Wall” as album, brief Pink Floyd show, film and even Berlin concert were collaborative efforts. The album was a band/producer work. The show was a combined effort of cast and crew. The film was headed by a strong-willed director. All of the works were composed by the creative bulldozer whose efforts in the decade thusfar were responsible for chart success, 20 million albums sold, and an artistic respect unsullied by thoughts of “If everyone likes this, it can’t be so good.” (That composer Roger Waters might have, by this time, been one the most disagreeable humans in history does not enter into the equation.)

Even the Berlin production of “The Wall” seemed more gimmick than art, with its guest performances and improbable nature. (The production only existed because Waters had [jokingly, I’d thought] said he’d remount the show when the Berlin Wall fell.)

But by the time the 21st century “Wall” was being presented to a wild- and wide-eyed little Timmy Cain in St. Louis, everything we were seeing was Waters’ idea. It was “Roger Waters’ ‘The Wall’.” Everything but Waters was relatively faceless, and certainly allowed no personality.

That was and is fine. As presented, the story of “The Wall” is one that Roger Waters has to tell us. Fascinating that the story that touches so many millions so deeply was changed ever-so-slightly, and we as an audience certainly needed Roger Waters there as a guide. Had the story changed so completely? (Well, yes, kind of at first, and then wholly, definitely and mind-blowingly.) If it could be changed that way, did we need Roger Waters there, or could it have been presented by a faceless theater company with an attractive leading man? (Well, yes, it could have been. That would have been an interpretation that had occurred to apparently exactly no one for the 30 years after “The Wall” was released. So whose interpretation was it? And whose voice and face did we need to ground us in the knowledge that this was the same story?)

(The answer, by the way, is that big-nosed bloke in his late 60s, the guy playing bass for half the show.)

Waters’ name is all over the credits of the film. Producing, directing, writing, everyplace a key creative name can be placed, Waters’ name is there. As it should be. Waters spent too much of his creative life sharing too much credit. I’ve liked enough of his stuff for enough of my life to come to a singular conclusion: Roger Waters is the creative force behind Pink Floyd, and the only reason any of what they produced has any lasting artistic merit or quality. Disagree with me on that one? You’re a big David Gilmour fan? That’s cool. Nothing Gilmour’s Pink Floyd produced ever had a bit of resonance with me. Heck, I even think “The Final Cut” is largely a crap album, rescued with a couple of decent songs tossed away while Roger Waters looked ahead to his next career step, without Pink Floyd.

So this is no complaint or indictment of Waters stamping his name all over the 21st century tour, or the documentary. But it’s intended as a reminder. It’s touching and heartbreaking on the surface, yes, to see Waters tear up while sitting in his car and reading the letter Waters’ mother received during World War II, the letter that assured her that her husband (and Roger’s father) had been killed in battle. The reaction may have been genuine, yes, but there are at least four different camera angles, and he (as writer/actor/producer) had to consent to showing his emotions to us in that manner. The same reminder is important when pondering Waters’ presence at the memorial at the battle site, or the shot of Waters with his family, pointing out the marker for his grandfather.

And if I’m going to criticize him for those conceits, I also have to praise him for an even greater conceit. On his way to the Battle of Anzio memorial, he drinks and tells a bartender (who doesn’t understand English) the story of the battle. A fantastic metaphor for both walls dividing us, and the uselessness of war.

“Everything has a meaning,” film co-director Sean Evans says. “He’s not into pretty pictures just for the sake of pretty pictures.”

3) And yes, Roger Waters was right about that

One of Waters’ complaints while sifting through footage of the shows was seeing the number of mobile devices in the crowd. He was baffled about how the crowd could get anything from his show when those cameras were just adding more bricks in the wall separating the audience from the performer.

But at those arena shows, a pre-show announcement didn’t discourage fans from using photographic equipment. The announcement merely and smartly asked that flash functions be shut off. My enjoyable memories of my arena show were enhanced by me locating full-length video from shows around the country.

Seeing the film, however, one can understand the complaints. In shots taken from overhead about halfway back from the stage, we see a sea of smartphones aloft. The light is distracting from the light onstage on which we should be focused.

That sea of smartphones was present at both shows I attended. (The pre-show announcement about photography being OK was not repeated, however.) The lights from the phones were not a distraction in person, however. It didn’t even bother me from people around me, and I’m certain I wasn’t bothering anyone taking the hundreds of photos I took.

I didn’t even have my hands in the air as often as those around me (many of whom were also taking photos) who pumped their fists in the air with every new song. (In some cases, I had to think, “You guys knew this song was coming next, didn’t you?”)

That’s Waters’ issues with his audience in a microcosm. It’s part of what sparked creation of “The Wall.” Waters had both the fortune and displeasure of having his fragile art be loved by millions. He might have preferred to perform “Pigs on the Wing” in a coffeehouse in front of a few dozen quiet and attentive listeners. But that wouldn’t accommodate the giant flying pig, so Pink Floyd had to play arenas like the one in Montreal, where Waters lost his temper onstage on the band’s “Animals” tour.

So often, Waters seems of two minds about his audience. He loves them, wants to communicate with them, wants to commune with them. At the same time, the faceless and fascistic nature of huge rock shows makes everything faceless – faceless performers heading a spectacle for a faceless crowd.

“The Wall” The Film shows some of that. The camera drifts by crowd members in slow-motion, making both poetry and mockery of fans’ delight at seeing Waters, or hearing their favorite song, or being present. Images of hundreds of people feeling that warm thrill of confusion, that space cadet glow.

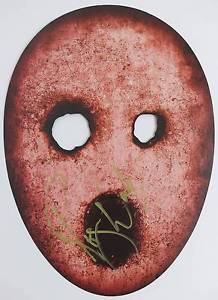

Waters also takes advantage of those fans. A group wears “Pink masks.” He uses fans’ enthusiasm to turn the rock-as-fascist-spectacle back on its head. He puts on his Nazi gear and hoists his hands above his head, wrists crossed in submission. It’s not an accident that Waters demands the audience participate, and exhorts “Enjoy yourself!” during “Run Like Hell.” Waters himself, like the corporations and organizations he satires elsewhere in “The Wall,” is a brand name demanding fealty.

4) Side three

When talking with a younger friend about Van Morrison’s “Moondance” album, I said side one is arguably the greatest album side in history.

“What’s a ‘side’?” my friend responded.

The first half of Act Two in “The Wall” – from “Hey You” through “Comfortably Numb” – that is a “side.” And it may be the greatest side in album history.

The problem is, “The Wall” Side Three is difficult to identify as a “side.” It’s bookended by two of Pink Floyd’s greatest songs. “Comfortably Numb” is certainly one of my five favorite songs, maybe one of my top three. I love the album, and have lived with it for decades. There are 30-cut albums (like The Beatles’ “White Album”) that I can recite in order, or in backward order, or (given a little time) in alphabetical order.

I can come up with the songs that populate the “middle” of Side Three, but only after some thought, and I’m not certain I can get them in order. They flow perfectly together within the work. But for much of my purpose, those songs have always been a postlude to “Hey You” and a prelude to “Comfortably Numb.”

So perhaps I was most susceptible in this specific area of the work. The stage production raises the stakes of those songs. “Is There Anybody Out There?” originally had struck me as another version of the rumbly, grumbly, synthesizer-air raid siren noise that concluded “Welcome to the Machine,” or Waters’ version of Frank Zappa’s “Who Are the Brain Police?” Instead, I came to realize and hear it as a fragile and beautifully crafted piece of music, an antidote to the haunting “Hey You,” a song that’s even more haunting in a different and equally appreciable way.

Then comes the stretch where Waters takes your thinking and feeling and all of your intense emotions, and he twists them out and wrings them dry. Repeatedly.

(If your emotions are not wrung by the footage of the shocked girl wearing the peace-sign earrings, I suspect you may be bereft of feelings. And if that one gets you, be prepared. It’s going to get worse.)

“Bring the Boys Back Home” always seemed wholly out of place in “The Wall.” If it’s a flashback, or a hallucination, it doesn’t work like that for me. It always felt like a piece Waters had and wanted to cram in somewhere. It belongs more on Side One, where Pink realizes his father’s death, rather than being a scene in which Pink seeks in vain for his father as the trains return. Or something. It was always the pothole on the road I had to drive through as slowly as possible in order to get to “Comfortably Numb.”

With the stage production, that changed. I was unaware of Dwight Eisenhower’s 1953 Chance for Pease speech. When I saw the following quote, Eisenhower elevated on my list of favorite presidents. (Let the clip continue to play to see how it’s presented. It follows immediately.)

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed.

It was depressing to realize nothing had changed from what Eisenhower had observed 50 years earlier.

(I found myself so emotionally taken with the moment at Wrigley that I was crying and shaking to the concern of those around me. I had to assure one man I was all right, and another slapped me on the back and said, “You a vet, man? Yeah, this is tough.” That kind of brought me back to reality, as I said, “No.” “Oh,” he responded. “Then you got a kid over there. Yeah, I hope he comes back all right.” Not that either, but thanks.)

And after all that, I get “Comfortably Numb”?

At my first live show, I found myself getting more and more tense and involved throughout Side Three. By “Comfortably Numb,” I realized there had been a gradual increase in volume, a touch that increased the intensity I was feeling. I was prepared by the second show, and put in earplugs at the end of “Bring the Boys Back Home.” (This also gave me the chance to surreptitiously wipe away a couple of pools of tears.) During the film, I inserted the plugs at the start of the second act.

Hey, if I don’t have my ears, I don’t have anything.

By the way, as long as we’re on the subject of “Comfortably Numb,” let’s make this clear. There are people who maintain the song’s first guitar solo in the best guitar solo in history. It’s not even the best solo in the song. Waters is correct in his decision to not change a note, to treat the solos as classical music compositions to be reproduced, not “improved upon.”

As one more note about the live show content: I was so amazed at Waters’ ability to sing “The Trial” that it took me some time to realize he wasn’t lip-syncing the Floyd recording. The only reason I quickly realized he was singing live was his inexplicable decision to change the girlfriend/wife’s voice to one with a horrific French accident.

I’ve had a lot of help with this part. It shows a whole other level of art in “The Wall,” and in Rogers’ oeuvre.

There are several things that turn up repeatedly in Frank Zappa songs. Dogs (specifically poodles), vacuum cleaners and chrome pop up in various contexts, along with a series of fictional characters created by Zappa. He called the practice “conceptual continuity,” choosing to advance the theory that the entirety of his art – recorded work, writings, live performances, even interviews – were all parts of a bigger whole. Zappa never really gave a meaning for the practice, or any reason for its importance. But it’s part of his art. Waters has shown a similar interest in deeper meaning.

“The Dark Side of the Moon” begins and ends with a simulated heartbeat. The album is infinite, a Mobius in its very existence. I had three copies of the album in high school to better show how the front and back covers connected, conceivably infinitely.

Until it became the stuff of Internet shared knowledge, I was unaware of “… where we came in” being the first sounds on “The Wall,” and “Isn’t this …” being the final sounds. It’s a nice loop.

The same loop is created with the documentary, which starts in what appears to be an underground parking garage. Waters says, “Where we came in.” And the final sound, as Waters has departed the stage and is about to get into transportation, he says, “Isn’t this …” One of the people at the film pointed it out to me. I was astonished, both that it was there and that I, now fully aware of the Easter egg on the album, missed it in the film.

Improbably, this has made me ponder a position flip on the great “Dark Side of Oz” debate. The theory states Pink Floyd’s “The Dark Side of the Moon” is intended to sync up with “The Wizard of Oz.” I’ve always found this to be a steaming, albeit extremely amusing, pile of dog doo. The band members and even engineer Alan Parsons have denied the connection. I’ve always believed the denials. If you’ve done something that clever, why would you not brag about it?

The flip side of the argument maintains that Floyd had no idea “Dark Side” was going to become one of the all-time album standards. How or why could they have? And they wouldn’t have had the resources to accomplish the task.

The beginning and ending of the documentary have me wondering about Roger Waters and his own conceptual continuity, and whether “Dark Side of Oz” might actually exist.

6) We’re still missing something

Had I been directing “Roger Waters The Wall” The Film, I would have made different decisions. In a couple of points (specifically during “Run Like Hell”), a number of Apple-related “I”-phrases pop up on the wall projection. (“iProtect,” “iBuy,” “iDecide”). In performance, these appearances are numbing. The world being created within the piece is increasingly frightening. We’ve been observed by drones, a huge inflatable pig is floating above the crowd, and these new words are taking us into a new world.

These are not shown nearly enough in the film for my satisfaction. In the most puzzling decision, most of the flower clip from “What Shall We Do Now” is shown, but there’s a cutaway from the video before the climactic violation. Why?

The scenes of the things happening onstage that I couldn’t see or never considered while sitting in the crowd bring a new appreciation to the technical nature of the work. I couldn’t count how many times I saw two- or three-step stairs, leading up and down the assorted levels of the set. The costume changes are more apparent. I had no idea how much Waters actually plays bass during the show.

Maybe one of the main points of the documentary is intended as peeks behind the curtain. We’re shown how it begins and ends offstage, Musicians get close-ups. Most intriguing for me were the overhead shots, pointed from along the wall down toward those on the stage.

Those overhead shots don’t give away all the secrets. I’d like to have seen more of the cherry pickers that put a singer and guitar soloist perched above the wall.

But I guess I have to give Roger Waters credit for one thing above all else. He knows how to tell the story way better than most of the rest of us do.